Saving Winter Squash Seeds

February 24, 2019 | Seeds and Seed Saving | 3 Comments

Saving squash seed is kind of an all-year affair.

The actual saving of seeds, for us, is mostly happening in February and March, as we want to select for squash that is long-keeping, which means not saving the seeds from squashes that go soft early in the year. We do save seeds from named varieties that are known long-keepers, even if we eat them in, say, November; however, we weight our seed saving efforts towards the survivors that are still hanging in there by this time of year.

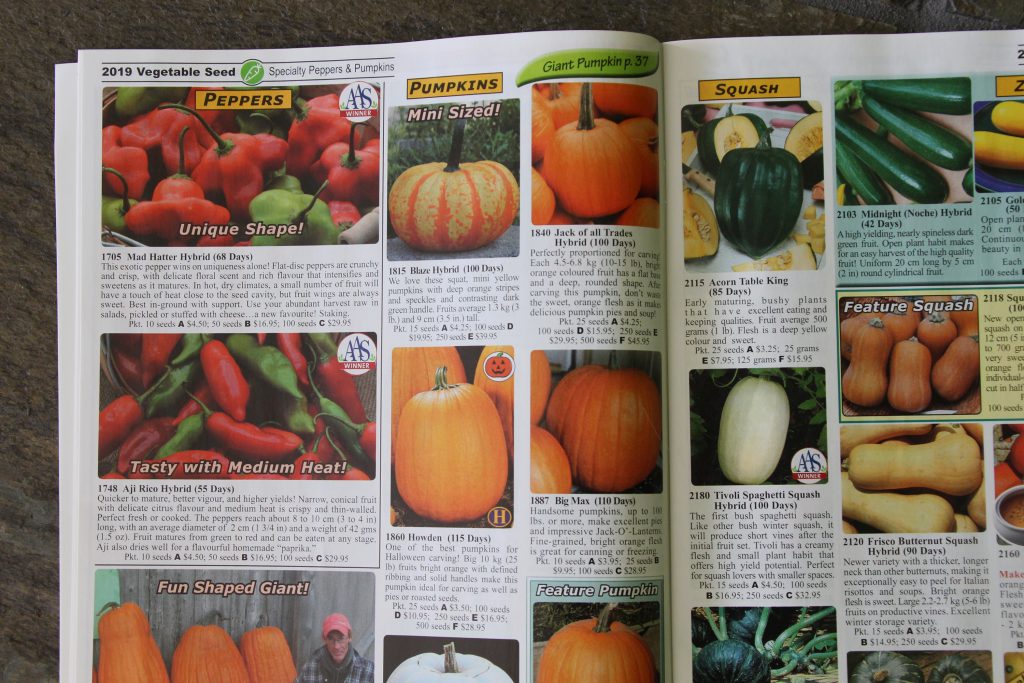

If you want your saved seeds to produce squash that resemble the parent plants, it is important to choose varieties that will come true from seed. Hybrids, which are crosses between different squashes from the same species, do not come true from seed – your seeds might grow something similar to one or the other parent, but won’t necessarily be the same as the squash you saved your seeds from. Hybrids often have more disease resistance, or bear heavier crops, so lots of gardeners like them; they just don’t make the best choice for saving seeds from.

Heirloom varieties typically come true from seed. That means that if you grow a particular type of pumpkin, for instance, and save the seeds, your seeds will grow pumpkins that are the same as the original plant…as long as those pumpkins were not cross-pollenated by a different variety of the same species.

You can learn more about the difference between heirloom and hybrid seeds here.

In order to keep varieties pure, you need to pay attention to what sorts of squash you are planting in your garden. There are four species of garden squash: curcurbita pepo, curcurbita moschata, curcurbita mixta, and curcurbita maxima. They do not cross with each other, so you could theoretically grow four different squash varieties (one of each type) and get pure seeds from each of them. In practice, it is more complicated, at least for us, as three of our favorite squashes (pie pumpkins, spaghetti squash, and zucchini) are from the same species (c. pepo), meaning they will inter-breed.

There are ways to keep your seed strains pure, even if you are growing several squashes from the same species. This involves taping the female flowers shut, so they cannot open, then carefully peeling them open and pollenating them with a male flower of your choice, before taping the female flower shut again, allowing the fruit to develop without any new pollen being added to the mix. We have not tried this yet – gardening with children makes it very difficult to deal with careful timing and delicate close work. You can find good descriptions of hand-pollenating squash here and here.

The other way to keep your seed pure, is to plant only one type of squash from each species. We have done this before, with great success. We always plant several types of c. pepo, as we just can’t imagine trying to get through a year with no pie pumpkins, or no spaghetti squash, or no zucchini. However, we have some favorite types of long-keeping curcurbita maxima squash that we have planted one at a time. Our current favorite heirloom c. maxima squashes are Red Kuri and Sweet Meat.

We haven’t had any luck growing

butternut-type squash like c. moschata here, as our season is so

short; however, we’ve joined up with a breeding project that will

hopefully (eventually) produce a c. moschata that will mature fruit

in our cool 90-day season. We’ve never tried a c. mixta squash,

though it is bound to happen eventually!

We tend to alternate

years for seed saving efforts; some years, we grow only one type of

c. maxima squash, and we can then save pure seed from that. Other

years, we grow a bunch of different squash types. We still save the

seeds from the crossbreeds, and grow them out; the results usually

taste quite good, and over time, by saving seeds from the tastiest

and longest-keeping squashes, we will develop a strain of squash that

tastes good to us, keeps a long time, and grows well in our

particular environment.

The actual seed collection and saving is pretty straightforward for squash. When you are ready to cook the squash, cut it open and scoop out the seeds. The seeds are attached to stringy flesh; rub this between your hands to get as much flesh as possible off of the seeds. Then, put the seeds in a dish or cup of water, and let them soak / ferment for a few days.

Once the remaining flesh falls off the seeds with rinsing (or they begin to smell – usually a few days, depending on the temperature), pour them out and rinse them thoroughly, rubbing them through your fingers to clean them off as much as possible. Then dry the seeds on a parchment-lined cookie sheet, stirring them from time to time. When the seeds snap when you bend them (instead of bending), they are dry enough to store.

At that point, I pick out the plumpest, most nicely-shaped seeds to save, and feed the rest to the chickens, as we always end up with way more seeds than we could ever use!

Squash seeds stay viable for quite a long time – five years or more if they are kept cool and dry, so you can save seeds one year, then use them for several years. I usually store my saved seeds in plastic baggies in a box in the bottom of a cool closet in our spare room.