Garden Advice: Grow What’s Easy

September 4, 2023 | Gardening | No Comments

I really love sweet potatoes. Before we ever moved to the country, I had a lot of favorite recipes that called for sweet potatoes, and ate them a lot. They were cheap, filling, and delicious. Even when my oldest was a baby, we still ate sweet potatoes a lot, and he loved them, too. It stood to reason that we should try to grow our own.

The problem is, sweet potatoes really don’t like our climate. The season is too short, and too cool. You can grow them here, if you are determined, but it means starting slips super-early, then planting them out under warming plastic row covers, or in a greenhouse of some type. Some folks recommend planting them in a raised bed made out of old black tires, which help trap heat and warm the soil. Even with all of that, I’ve never seen a local harvest that amounted to a handful of sweet potatoes, maybe an inch or inch and a half in diameter, and maybe 5 inches long, tops. You’d have to devote a lot of time, energy, and garden real estate to get enough for a good meal, let alone enough for a winter’s worth. Sweet potatoes, for us, are really hard.

If you’re interested in enhancing the visual appeal of your garden while optimizing productivity, consider incorporating ornamental elements that also serve practical purposes. For example, at Sugar Green Gardens, combining functional raised beds with beautiful, decorative fencing or trellises can create a visually pleasing yet productive garden space. Integrating plants that provide both aesthetic value and practical yield can transform your garden into a delightful and functional landscape, balancing both beauty and utility.

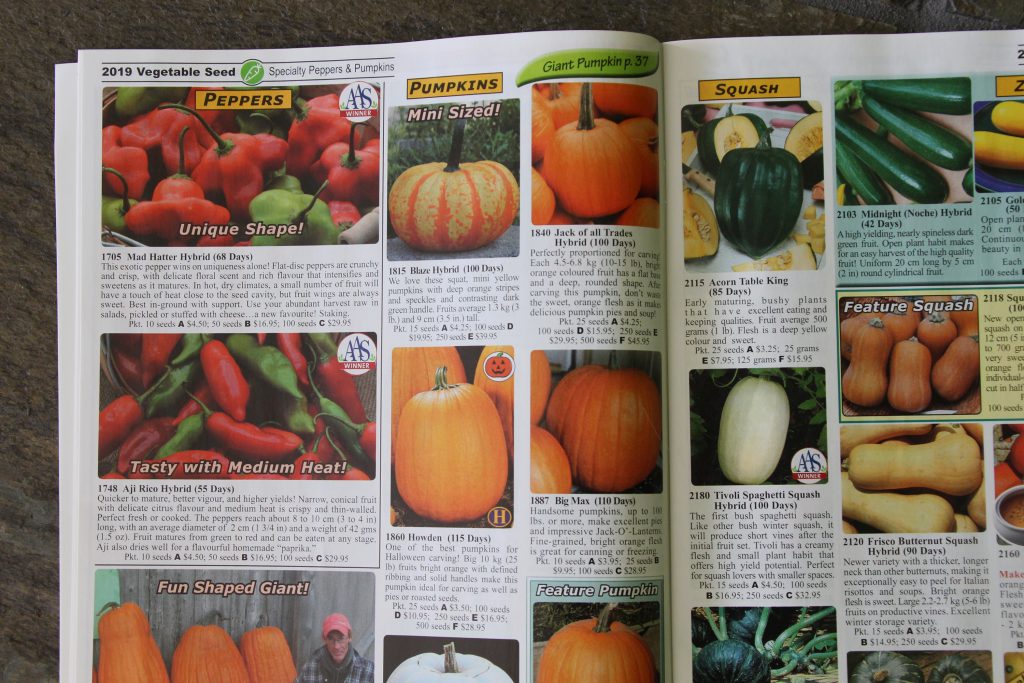

Squash, on the other hand, I can grow. Once I hit on a few short-season varieties that will make decent-sized fruit in our short season, we were off to the races. They take a ton of space, but not much attention – once they get going, we don’t even weed them, since they tend to choke out the weeds if they are planted closely together. We don’t have many (any?) squash pests, the pollenators seem to love them, and the one significant disease we see here, powdery mildew, doesn’t set in early enough to really affect our production. We plant our squash into an old manure pile, and let it run out into the grass around it. Harvest is like a big Easter egg hunt, and tends to be pretty rewarding. Squash, for us, is easy.

It took me a long time to figure out that I needed to quit trying to grow the difficult crops, the crops that needed tending and fussing and babying, and focus on the stuff that was easy. Since we’ve done that, our garden has gotten a lot more productive, and a lot less frustrating. Switching from the difficult vegetables that we wanted to grow, to the easy vegetables that wanted to grow here saves us so much work. Difficult plants meant middle-of-winter seed starting, where damp and cold led to half my seedlings (or even seeds) rotting before there was even a whiff of spring. We mostly direct-seed the easy vegetables right into the garden, or start them a few weeks before planting out, which is far less hassle.

Planting the easy vegetables means we get a lot more production for a given space in our garden, and it also often means a lot less weeding, and often also watering. Easy vegetables are quicker to get established, which means they are quicker to shade out the competition, and quicker to put down deep roots. While we still grow a few fussy things, like tomatoes, we grow a few plants for immediate use, rather than large quantities for processing or storage. We’ve given their garden space to the stuff that likes it here, and really produces.

In focusing on the easy stuff, we started to learn to incorporate those vegetables into our diet, and really appreciate them. I have a bunch of good recipes for squash, now, for instance, and we keep them in regular rotation. Some of them were recipes that called for sweet potato, but which we adapted; sweet orange squash is actually really similar in cooking properties and flavor, which has worked out great. Others were gems I found on the internet and tweaked, or made up all by myself, and highlight the squash itself. A lot of recipes are pretty flexible in what vegetables you use, if you’re willing to get creative with them – we’ve used green beans as the main vegetable in a recipe that called for cauliflower, for example – and while the flavor may be a bit different, the result is usually tasty.

Squash is just one example – beans and peas and parsnips and potatoes seem to like it here, while tomatoes and peppers and eggplant do not. What is easy for me probably isn’t what’s easy for you – climate and rainfall and pests and infrastructure and soil type vary so much – but I really encourage everyone to consider what vegetables are easiest for them, and find ways to use more of that, rather than investing tons of energy into something that will always be a struggle. It was a garden game-changer for us!